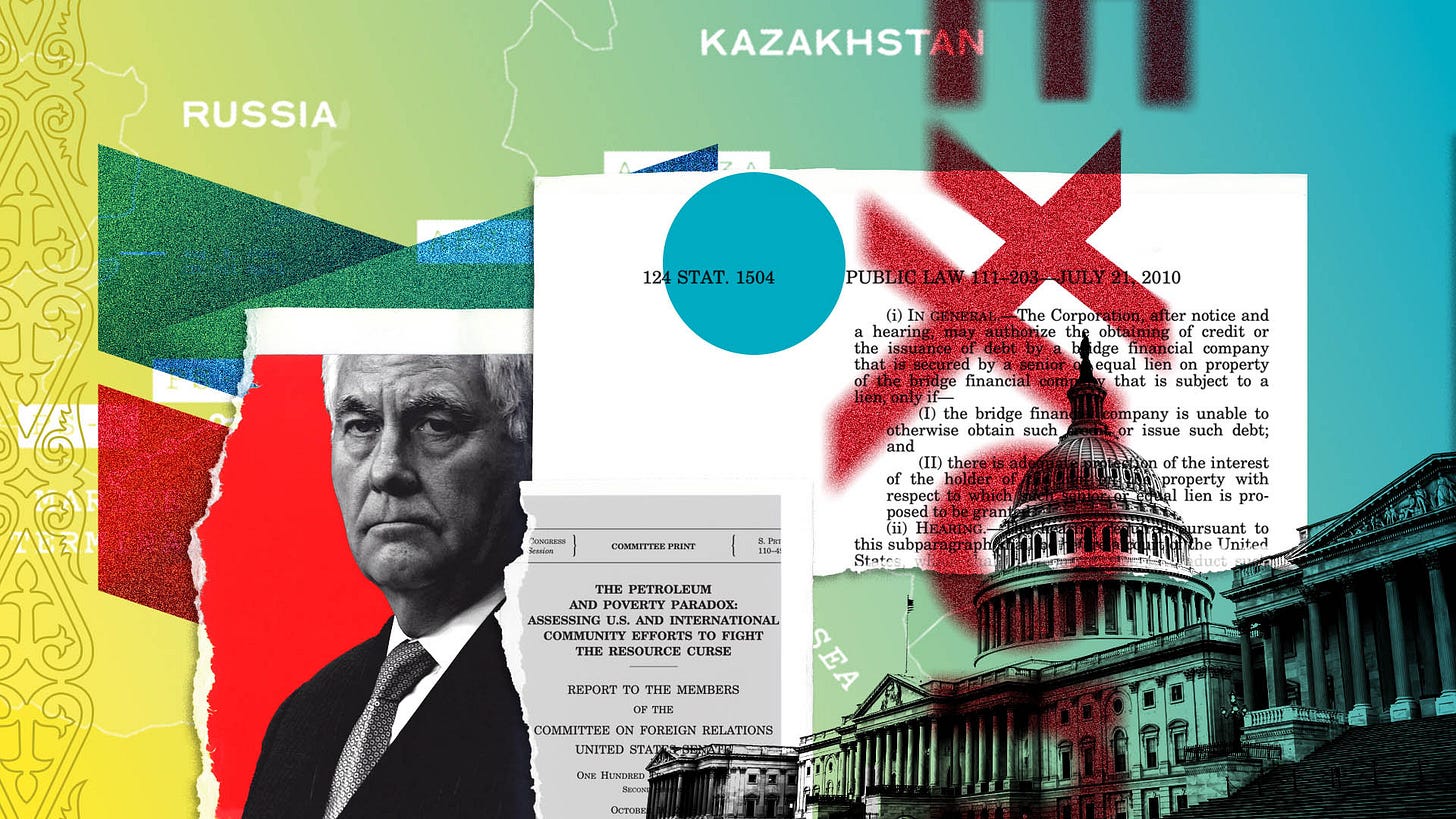

Report: Inside Big Oil’s War Against Transparency

For a decade, the industry fought bitterly against a basic anti-corruption rule to report their payments to foreign governments.

Image Credit: ICIJ

Courtesy: International Consortium Of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ)

That afternoon, the U.S. Senate voted 56-43 to confirm him to be secretary of state. The recently retired ExxonMobil Corp. CEO was sworn in at the White House a few hours later with his wife and President Donald Trump at his side.

But there was another vote that day that was consequential in Tillerson’s career — and for the political fortunes of Exxon, which had sizable holdings in Russia and investments in other undemocratic countries. The House of Representatives voted to kill an anti-corruption, pro-transparency rule that the oil industry — and Tillerson personally — had been fighting in different forms for years. The Senate followed suit a few days later.

The rule, mandated by an amendment to the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act and issued by the Securities and Exchange Commission, would have required oil, gas and mining companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges to publicly disclose their payments to governments where they operate, both overseas and domestically.

The amendment’s bipartisan co-sponsors, Sens. Ben Cardin, D-Md., and the late Richard Lugar, R-Ind., believed it was in the U.S.’ interest to help the billions of people living in resource-rich countries to stop their rulers and elites from diverting oil, gas and mining wealth from public coffers to enrich themselves. They thought disclosing company payments to governments would undermine the secrecy that enables kleptocracy to flourish.

Transparency and anti-corruption groups worldwide such as Oxfam, the FACT Coalition, Publish What You Pay and EarthRights International supported the measure, and Canada, Norway and the European Union quickly adopted nearly identical rules.

But in the U.S., the Cardin-Lugar amendment set off a relentless, high-pressure lobbying and legal drive led by Exxon, Chevron Corp. and the American Petroleum Institute that would stretch over a decade. They challenged three versions of the rule in the courts and Congress, and at the SEC, where one former commissioner said he spent “half his time” with their lobbyists.

At the time, oil industry advocates argued that the price tag for implementing the original version of the SEC rule would be too much of a burden for companies; the agency estimated it would affect 1,100 firms and initially cost them a total of $1 billion. The industry also asserted that the rule would put U.S. oil companies at a disadvantage, potentially giving rivals a financial edge when negotiating deals.

As more companies complied with Cardin-Lugar-style disclosure rules in other countries, there was little evidence to support those dire predictions, transparency advocates said. But in the U.S., the epic lobbying blitz carried on, and in December 2020, during the waning days of the first Trump administration, the industry got the result it wanted. The SEC voted 3-2 to approve a weaker rule that no longer required disclosure of payments by contract and included more exemptions from having to report at all.

In most jurisdictions, natural resources are managed by the state on behalf of its citizens.

— Ian Gary, executive director of the FACT Coalition

The diminished rule’s inadequacies — and relevance — became clearer this year, the first year companies disclosed payments to the U.S. and foreign governments.

Transparency advocates said the watered-down rule still had value and will “further enhance the global norm of disclosing oil and mining company payments to governments,” Ian Gary, the executive director of the Financial Accountability and Transparency (or FACT) Coalition, told ICIJ. “In most jurisdictions, natural resources are managed by the state on behalf of its citizens. People have the right to know basic financial information about the sale of these non-renewable assets.”

But the current rule also allows companies to leave out key details. For example, Exxon, Chevron and other firms including Transneft, a Russian state-owned company, are partners in the Caspian Pipeline Consortium. CPC pays hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes and fines to Russian governmental authorities. These taxes help sustain the Russian economy, boost arms production and pay state officials’ salaries and pensions — thereby aiding the Russian war effort in Ukraine.

Yet in their first disclosures, filed with the SEC, neither company reported any payments to Russia. Under the rule passed in 2020, the companies don’t have to report payments made by a joint venture that they don’t directly operate.

In a statement to ICIJ, Sally Jones, a senior media adviser for Chevron, said the company is “committed to ethical business practices, operating responsibly, conducting its business with integrity and in accordance with the laws and regulations of each of the jurisdictions in which it operates.” Exxon did not respond to requests for comment.

The story of this drawn-out battle against a basic anti-corruption effort is part of Caspian Cabals, an investigation led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and 26 media partners into the rise of a critical pipeline in the Caspian Sea region and the Kazakh oil fields that feed it.

The two-year investigation is based on tens of thousands of pages of confidential emails, company presentations and other oil industry records, audits, court documents and regulatory filings, as well as hundreds of interviews, including with former company employees and insiders. Caspian Cabals shows how Western oil company money has empowered anti-democratic actors in Kazakhstan, bolstered the neighboring regime of Russian president Vladimir Putin and enriched regional elites. That includes Nursultan Nazarbayev, who led Kazakhstan from 1991 to 2019, during which multiple members of his family amassed multibillion-dollar fortunes.

The fight over the Cardin-Lugar rule showed the lengths to which some U.S. oil companies and their allies were willing to go to thwart greater transparency and to avoid closer scrutiny of their relationships with autocrats and kleptocrats. “It’s no wonder that Big Oil and its lobbyists fought tooth and nail to dilute U.S. regulations on payment transparency,” said Jana Morgan, the director of Publish What You Pay-US from 2013-2017. “They know that transparency exposes wrongdoing and holds both corporations and governments accountable.”

The Case For Sunlight:

The push in Congress to get oil, gas and mining companies to disclose their payments to governments dates back to 2008. That year, Lugar, then the ranking member on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, sent a dozen committee staffers to 21 countries to assess anti-corruption efforts in resource-rich nations, according to Jay Branegan, a senior staffer on the Senate panel who worked with Lugar.

“We found plenty of examples of the ‘resource curse’ countries with substantial oil or mineral deposits that were nonetheless doing poorly economically,” Branegan recalled. In some countries like Nigeria, the Senate committee staff members saw that poverty increased after the discovery of oil. They compiled their findings in a 119-page report titled “The Petroleum and Poverty Paradox: Assessing U.S. and International Community Efforts to Fight the Resource Curse.”

“This ‘resource curse’ affects us as well as producing countries,” Lugar wrote in a letter attached to the report. “It exacerbates global poverty which can be a seedbed for terrorism, it dulls the effect of our foreign assistance, it empowers autocrats and dictators, and it can crimp world petroleum supplies by breeding instability.”

Cardin, who served on the Foreign Relations Committee with Lugar and now chairs it, told ICIJ that the Cardin-Lugar amendment grew out of that research. “For a long time we’d been following corruption among certain countries with the extractive industries where the profits from the extractive industries were going to the leaders of the country or the power people of the country, and not to the citizens,” he said.

The lawmakers believed more transparency would make it harder for foreign leaders to skim off industry payments. They also believed it would help to stabilize markets and protect investors.

This ‘resource curse’ empowers autocrats and dictators, and it can crimp world petroleum supplies by breeding instability.

— Senator Richard Lugar, co-sponsor of the Cardin-Lugar amendment

Advocates for payment transparency also stressed the negative impacts of corruption on countries like Equatorial Guinea, a major oil-producing nation in Central Africa. Its vice president, Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, who is also a son of the nation’s longtime leader, relied in part on money from Western oil companies, including Exxon and Chevron, to amass more than $300 million in assets, according to U.S. prosecutors. While about 75% of its population of less than 2 million lived in poverty, he owned a $30 million home in Malibu, a fleet of luxury cars including Ferraris, Lamborghinis and Bentleys, and one of the largest collections of Michael Jackson memorabilia that included a $275,000 crystal-covered glove. Obiang also had a $124 million six-story mansion in Paris that contained a $1.8 million Louis XV desk, a Rodin sculpture and a dozen Fabergé eggs.

The stolen monies should have been used for education, roads and hospitals like the one Tutu Alicante’s sister went to in Equatorial Guinea in 1996 for an ectopic pregnancy. Alicante, now the executive director of the human rights advocacy group EG Justice, recalled at an October event with transparency groups that the hospital had neither electricity nor a doctor and his sister bled to death. “During those years my country, Equatorial Guinea, was referred to as ‘the Kuwait of Africa’ because of the amount of oil and gas that was being produced. Yet my sister, like hundreds of women in my country, … was still dying … due not to diseases or any illnesses, but rather due to entrenched, grinding poverty and inequality that was manufactured by the autocratic government in my country, supported by oil companies.”

In 2010, as the Cardin-Lugar proposal gained momentum on Capitol Hill, Tillerson, then Exxon’s CEO, flew to D.C. for a half-hour meeting with Lugar.

“Tillerson was the only oil company executive to come to Senator Lugar’s office personally to lobby against the proposed legislation,” recalled Branegan. “The fact that the CEO of a giant global corporation would personally lobby the senator showed us how seriously the industry regarded the issue.”

Branegan said Tillerson repeated “many of the oil industry’s arguments and also said that it would hurt Exxon’s relations with Russia.”

Tillerson and Exxon had extensive ties to Russia and Putin. Before he became CEO in 2006, Tillerson was a director of Exxon Neftegas, an offshore company in the Bahamas that was at the heart of Exxon’s close business dealings with Russia, according to leaked documents from the Bahamas corporate registry received by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared with ICIJ in 2016. Tillerson ended his association with Neftegas in 2001, a company spokesperson said.

In 2011, Tillerson attended the announcement in Sochi, Russia, of a $3.2 billion deal between Exxon and the Russian oil company Rosneft to open oil and gas production in the Arctic Ocean. At the signing ceremony, then-Prime Minister Putin said, “The scale of the investment is very large. It’s scary to utter such huge figures.” The following year, Exxon announced a $500 billion joint venture with Rosneft, and in 2013, Putin awarded Tillerson the Order of Friendship, a state decoration for foreigners whose work improves their countries’ relations with Moscow.

Attempts to reach Tillerson were unsuccessful.

Lugar told Tillerson during their half-hour meeting in 2010 they would have to agree to disagree, Politico reported. Cardin-Lugar was enacted that year as Section 1504 of the Dodd-Frank financial reform law. A phalanx of lobbyists for the oil industry and its allies had tried to block efforts to attach it to Dodd-Frank and, when that failed, eventually took legal action and stepped up their lobbying campaign.

“To discredit and weaken our position, they used every excuse imaginable,” Cardin told ICIJ. “They were very aggressive in the Senate lobbying against 1504. It was one of the heaviest lobbying efforts I’ve ever seen.”

Big Oil Goes To Court:

The SEC took two years to turn Cardin-Lugar into regulations, which the oil industry and business allies quickly challenged.

In October 2012, the American Petroleum Institute, the chief oil industry lobbying group, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and two other trade groups with strong oil and business ties filed a lawsuit against the SEC. They argued that the agency failed to adequately weigh the rule’s costs and benefits, and that the rule would reveal sensitive internal business information.

EugeneScalia, a partner at the white-shoe firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher in Washington and a son of then-Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, argued the case in court. By then, the younger Scalia had already won a case against a different Dodd-Frank agency rule and had notched victories against other SEC regulations.

In 2013, a U.S. District Court in Washington ruled in favor of API and the other plaintiffs, which sent supporters of the rule back to the drawing board to redraft it.

Michelle Harrison, deputy general counsel with EarthRights International, who was heavily involved in backing the original SEC rule, told ICIJ that the revised version was also “strong” and supported by many anti-corruption and pro-transparency groups. The SEC approved it in mid-2016. But once Trump took office in early 2017, the oil industry and business allies went back on the offensive.

In a letter dated Jan. 31, 2017, a day before the House voted to nullify the rule, then-API President Jack N. Gerard told lawmakers the rule was overkill. He argued that the 1977 Foreign Corrupt Practices Act already forbade companies from bribing foreign officials and that the new rule, combined with those prohibitions, would hurt U.S. firms’ competitive position. He complained, too, that the rule was not consistent with the agency’s mission of protecting investors and investigating fraud, and suggested the SEC unnecessarily took on a “social agenda issue.”

An API spokesperson declined to comment, saying the SEC rule is no longer an active issue for the group.

In an opinion piece in The Hill, published the same day Gerard sent his letter, Cardin and Lugar, who by then was no longer in the Senate, disputed the argument that the disclosures would reveal sensitive company information. They pointed out that many nations had embraced a similar rule and that some large oil companies like BP PLC, TotalEnergies SE and Shell PLC, plus some Russian oil giants including Gazprom and Rosneft, had already complied with disclosure requirements overseas.

Paul Pelletier, a former senior Justice Department official who served as acting chief of the Criminal Division’s fraud section, took issue with the industry’s argument that existing anti-bribery laws made further disclosure unnecessary.

“The [Foreign Corrupt Practices Act] forbids bribery by U.S. firms overseas to win business but doesn’t require disclosure of payments to foreign governments by U.S. companies,” he told ICIJ. The oil industry overlooked “the benefits of more transparency as the rule initially intended.”

Transparency advocates point to Ghana as a success story. Payments data influenced lawmakers there in 2016 to change royalty rates and capital gains tax rules for oil and gas production, which helped boost government revenues, according to Rob Pitman, senior governance officer with Natural Resource Governance Institute.

In Europe, where the original Cardin-Lugar proposal inspired countries to adopt similar disclosure rules, evidence was also starting to emerge that undermined the industry’s contention that undermined the industry’s claim the cost of implementing Section 1504 was burdensome. French oil giant Total would later report that its annual compliance costs in relation to a transparency directive and an accounting directive were about $200,000, a 2020 analysis by Publish What You Pay showed.

The [Foreign Corrupt Practices Act] forbids bribery by U.S. firms overseas to win business but doesn’t require disclosure of payments to foreign governments by U.S. companies.

Paul Pelletier, former senior Justice Department official Oil lobbyists and their business allies won the argument, though, with the only audience that mattered. They turned to three friends in Congress: Rep. Bill Huizenga, R-Mich., the late Sen. James Inhofe, R-Okla.; and then-Senate Banking Committee Chairman Mike Crapo, R-Idaho. The lawmakers employed a legislative tool called the Congressional Review Act to overturn the rule in February 2017 in the House and Senate. Trump signed the regulatory disapproval measure soon after.

Crapo and Huizenga did not respond to requests for comment.

At his confirmation hearing a few weeks earlier, Tillerson was asked repeatedly about his commitment to transparency and fighting corruption.

He told lawmakers: “During my tenure as chairman and CEO, ExxonMobil strongly supported efforts to increase the transparency of government revenue from the extractive industries.”

Several senators also asked him about the energy company’s operations in Equatorial Guinea. In 2004, the year Tillerson became a director and president of Exxon, it was one of four oil companies questioned by the SEC over their payments to the Obiang government. The inquiry followed a 2004 Senate subcommittee report on money laundering at Riggs Bank, where Obiang and his family members had multiple accounts. The report said Exxon started an oil distribution firm in Equatorial Guinea in 1998, 15% of which was owned by Abayak S.A., a company controlled by President Obiang, his wife and son. During his confirmation hearing, Tillerson said a congressional inquiry did not find evidence that Exxon committed wrongdoing.

He went on to say the company’s contracts with foreign governments were no different than ones used for projects on federal land in the U.S. “There is royalty and there are taxes paid to the … Treasury,” he said. “What the government does with those monies once the company pays those is up to the government.”

An Industry-Friendly Rule:

After Congress killed the second version of the SEC rule, the agency began to revise it once more as it was required to do by law, a process that took nearly three years and sparked another wave of lobbying.

Former commissioner Robert Jackson, who served at the agency from 2018 until early 2020, told ICIJ he spent half his time meeting with lobbyists for the oil companies. He said the industry and its allies approached him with a “sense of legal entitlement.” They seemed to think incorrectly, in Jackson’s view that Congress killing the previous version “mandated a weaker rule.” Confident the courts would back their position, “the Chamber often threatened to sue the SEC,” he recalled. (A spokesperson for the Chamber declined to comment.)

The rule remained a top priority for Exxon executives. Darren Woods, who took over as CEO of Exxon in 2017, even traveled to Washington in November 2018 to meet with then-SEC Chair Jay Clayton. Clayton did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

By 2020, the SEC had drafted a third version that was much more favorable to the industry. Cardin and other transparency advocates criticized it as too lax. Jackson, who worked on it but left the SEC in February that year, said the final rule was so watered down it provides “almost no meaningful sunlight.”

A key sticking point was the way the rule defined exactly what oil companies were required to disclose about their foreign payments. It exempted disclosures of oil payments below $150,000, where transparency groups say corruption often occurs. And rather than having to itemize their payments by each contract or project for greater transparency, companies were required to report aggregate payments only by country or political jurisdiction. The rule also added two exemptions for “situations in which a foreign law or a pre-existing contract prohibits the required disclosure.”

On Dec. 16, 2020, the commission approved the industry-blessed rule by a vote of 3-2, with Jackson’s successor, Caroline Crenshaw, and fellow commissioner Allison Herren Lee dissenting.

“In the end, it’s hard to understand who we are serving with this final rule,” Lee said in a statement that day. “We are not effectuating Congress’s intent in passing Section 1504. We are not ensuring sufficiently granular disclosure to enable citizens to combat corruption. We are not providing investors with the information that is material to their investment and voting decisions. We are not heeding the numerous calls from issuers who have asked us to harmonize our rules with the international standard. And, most unfortunately, we are not taking the opportunity to further the SEC’s and the United States’ tradition as leaders in the fight against global corruption.”

In its Section 1504 filing, which covers fiscal year 2023, Exxon reported that its largest payment went to the United Arab Emirates ($7.4 billion), followed by Indonesia ($4.6 billion). It paid the U.S. $2.3 billion. Exxon also said it paid $12.2 million in taxes and fees to government entities in Kazakhstan. Most of it went directly to a government tax collector and the rest to the state-owned pipeline company.

Chevron listed only a total payment for each country. Its largest payments went to Australia ($4 billion) and Nigeria ($3.2 billion). It said its payments to Kazakhstan totaled $152.7 million.

Neither Exxon nor Chevron reported any payments to Russia for 2023 despite their stakes in the Caspian Pipeline Consortium, which pays Russia taxes and fines. In 2022, CPC paid about $321 million to Russian authorities, including $96 million in taxes and fees to the federal government. It also paid a $98.7 million fine as a result of an August 2021 oil spill.

The companies don’t have to report payments made by a joint venture that they don’t directly operate, nor do they have to disclose how much they reimburse the operator for their share of the payments to governments. Exxon and Chevron did not respond to questions about their disclosure filings.

Zorka Milin, FACT’s policy director, told reporters at a press briefing a few weeks after their release that the disclosures showed Big Oil was not invincible. “On this issue they threw everything against it. They had high-powered lawyers and lobbyists. They even dragged the Chamber of Commerce into it. And yes … they did have some legal and political victories along the way, but in spite of it all we’ve got these disclosures which they never wanted to see the light of day.”

[In] spite of it all we’ve got these disclosures which they never wanted to see the light of day.

– Zorka Milin, FACT Coalition policy director

Aubrey Menard, Oxfam America’s senior policy adviser for natural resource justice, also described the disclosures as “a major victory for civil society and very revealing about the industry’s payments.” But she told ICIJ they have “some significant gaps as a result of Big Oil’s decade-long campaign to water down the final rule.”

The SEC rule does not require the companies to report payments for projects or jurisdictions within countries, she continued, making the disclosures less useful. “It does little good to have one aggregate number for all payments lumped together so that you cannot see which is for what project or to what state,” Menard said. “It makes it impossible to analyze the utility of a single project or whether citizens are receiving what they should in exchange for their natural resources, or for investors to evaluate a project’s worth and risk.”

Menard noted critically that in its disclosure, “Exxon includes a long preamble about all the payments that they’re making that they aren’t required to disclose under the SEC rule, including taxes, fees and duties paid to local, state and federal governments. But since they’re declining to disclose this information, are we just supposed to trust them on those?”

The current version of the disclosure rule may not be the last one. The agency has included it on its rulemaking agenda for several years as a possible target for review but hasn’t followed through.

Cardin, who is retiring when his term ends in January, said he has not given up on strengthening the rule. In a September letter, Cardin pressed SEC Chair Gary Gensler on the agency’s failure to move forward.

The current rule is the law, Cardin wrote, but so is Dodd-Frank, and “I’m gravely concerned the SEC is failing to meet its legal obligations under Section 1504.” An SEC spokesperson told ICIJ the agency “does not comment on what regulatory actions the Commission may take in the future” beyond the public rulemaking agenda.

The version that is now in effect, Cardin told ICIJ, can’t be allowed to stand. The regulations are “better than nothing, but they protect the oil companies and the corrupt leaders.”